Human Eyes: Everything You Need to Know

The eyes are one of our most vital sensory organs, and none are as complex as the eyes. The human eye can absorb and instantly process over ten million pieces of information per second. But have you ever wondered how the eyes work? How are the images we see created? Which parts of our body are involved in this intricate process? This guide provides all the detailed information you need, covering the anatomy, structure, and performance of the eyes.

The way our eyes function is similar to a camera. Simply put, different parts of the eye work together to allow us to see the world around us. Keep reading to discover how the eyes work. First, let's discuss the essential parts of the eye and their structures.

Anatomy: The Structure of the Human Eye

Cornea

- The cornea, located on the outer layer of the eye, is kept moist by tears. It is embedded in what is known as the sclera (the white part of the eye); together, they form what experts call the outer shell of the eyeball. The cornea acts like a window: it is a transparent disc that allows light to enter the eye. It also protects the eye from external influences like dirt, dust, or surface injuries. The cornea is elastic, and more importantly, its curvature gives it optical properties that play a crucial role in helping us see clearly.

Sclera

- The sclera (the white part of the eye) is thicker and tougher than the cornea, providing protection against injury. It covers almost the entire eye, with two exceptions: the cornea embedded at the front and the optic nerve fibers at the back.

Pupil

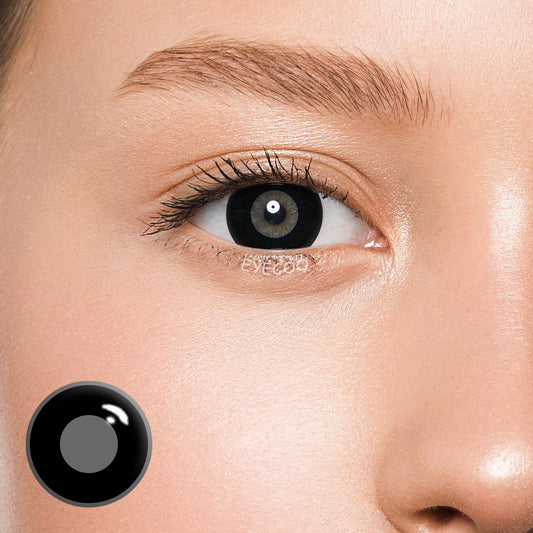

- The pupil is the black part at the center of the eye. It reacts to incoming light and adapts to its intensity. However, it is not the pupil itself but the iris that controls this function. Our emotional state can also affect the size of the pupil. For instance, fear and joy can cause our pupils to dilate, and substances like alcohol and drugs can also alter their size.

Iris

- The iris is a colored ring surrounding the pupil, functioning like a camera aperture to control the amount of light that enters the eye. In bright environments, it makes the pupil smaller to reduce light entry, while in darkness, the opposite happens: the pupil dilates to allow more light in. The iris also determines our eye color, and each person's iris is unique. Interestingly, the color of the iris has no effect on vision. People with brown eyes do not see the world "darker" than those with lighter eye colors like blue.

Chambers of the Eye

- The eye is divided into the anterior and posterior chambers. The anterior chamber is a space filled with aqueous humor. This fluid contains essential nutrients needed by the lens and cornea; it provides oxygen and helps them fight off pathogens. The aqueous humor in the eye chamber also has another function: it helps maintain the eye’s shape.

Lens of the Eye

- The lens of the eye gathers light entering through the pupil, ensuring that the image on the retina is clear. The lens is flexible and can adjust its shape using the ciliary muscle to focus on objects near and far. This means that when we look at something up close, the lens bends to provide a clear vision. When viewing distant objects, the lens flattens to help you see clearly. The lens inverts and reverses the image onto the retina, which is later corrected when the brain processes the image.

Ciliary Body and Trabecula

- The ciliary body plays a vital role in our vision: it produces aqueous humor and contains the ciliary muscle (musculus ciliaris). By adjusting the lens, it ensures that we can focus on objects both near and far.

Vitreous Body

- The vitreous body is located between the lens and the retina. It makes up the majority of the eye, and as the name suggests, it represents its structure. The vitreous body is transparent and consists of 98% water, with 2% sodium hyaluronate and collagen fibers.

Retina

- The retina processes light and color stimuli and transmits these to the brain via the optic nerve. In simple terms, the retina acts as a catalyst: it converts incoming light using sensory cells and then passes it on to the brain for processing. These sensory cells are made up of cones (for viewing colors) and rods (for detecting light and dark). No part of the eye has more sensory cells than the center of the retina or the macula: about 95% of photoreceptor cells are concentrated in an area of approximately 5 square millimeters, which is about the size of a pinhead.

Choroid

- The choroid is located between the sclera and the retina, behind the iris and ciliary body. It ensures that the retina’s receptors receive nourishment, maintains a consistent temperature for the retina, and also plays a role in the regulation of vision between near and far distances, almost like how a camera lens focuses.

Optic Nerve

- The optic nerve is responsible for transmitting information from the retina to the brain. It consists of about one million nerve fibers (axons), is about half a centimeter thick, and exits the retina through the optic disc. This point is also known as the "blind spot" because there are no sensory cells in the retina there. That’s why the image created by the brain actually has a black spot, but in fact, small gray cells compensate for this, providing a consistent image. However, this spot is usually not consciously noticed as the brain “fills in” the gap.

Fovea

- Small in size, but with a big impact: the fovea is less than 2 millimeters wide, but it plays a crucial role in our visual system. It is located in the center of the retina and is surrounded by sensory cells that enable us to have sharp vision and see colors during the day. When we look at an object, our eyes automatically rotate so that it can be imaged on the fovea.

External Structure of the Human Eye

- The parts surrounding the eye also play an important role in our vision, including the eyelids, eyelashes, tear ducts, and eyebrows.

Lacrimal Glands

- About the size of an almond and located on the outer edge of the eye socket, the lacrimal glands produce tears when needed. Their secretions consist of salt, protein, fat, and enzymes, protecting the cornea and helping to remove foreign substances from the eyeball.

Eyelids

- Every time we blink, our eyelids moisten our eyes, and they reflexively close to protect the eyes from wind, liquids, and foreign substances. On average, people blink eight to twelve times a minute, and tears spread across the eye surface in a fraction of a second. This moistens the cornea and prevents it from drying out.

Eyelashes

- Not only do eyelashes look beautiful, but they also serve a practical function: they prevent dust, dirt particles, and other foreign substances from entering the eyes. This all happens automatically: as soon as the eyelashes come into contact with something or the brain wants it to happen, the eyelids close as a reflex.

Eyebrows

- Eyebrows protect the eyes by preventing sweat from dripping into them from the forehead.

Vision Explained: How the Eyes Work

- The way we see things is part of a complex process: before we see something, a series of separate steps occur in the eyes and brain. We discussed the retina-cortex pathway, which begins in the eye and ends in the brain. In simple terms, vision works like this: the human eye absorbs light from the surroundings and focuses it on the cornea. This creates the initial visual impression. Then, each eye transmits the image to the brain via the optic nerve, where it is processed, resulting in what we call "vision." Light forms the basis of everything we see. In complete darkness, we are essentially blind.

More specifically, this means that if we can see an object, there must be light on that object. The light is reflected off the object into our eyes and processed by our visual system. If we look at a tree, our eyes absorb the light it reflects: the light first passes through the conjunctiva and cornea. Next, it travels through the anterior chamber and pupil. Then, the light reaches the lens of the eye, where it is focused and transferred to the photosensitive retina. The retina collects and organizes visual information: rods are responsible for light-dark vision, and cones are responsible for clarity and color. This information is transmitted to the optic nerve and then to the brain, which evaluates, interprets, and integrates it, ultimately forming the image we see.

Despite detailed studies of the anatomy and structure of the human eye, many questions about how consciousness works remain unanswered. So, while we know which parts of the brain are most active when seeing something, no one fully understands how we perceive the world.

Seeing Near and Far Objects

- Healthy eyes can do this automatically without any assistance, allowing us to switch between near and far distances and see objects clearly at both ranges. This dynamic ability to see objects clearly at different distances is known as accommodation. It is based on the flexibility of our eye’s lens. As long as the vision is undamaged, the lens can change its shape to adapt to either near or far objects, depending on what we want to see. In a normal eye, the lens is elongated, which is ideal for viewing distant objects. However, when we look at something up close, the lens bends: it switches to near vision and allows us to see the object clearly. When the image on the fovea becomes blurry, the lens adjusts.

Daytime Vision—How Does It Work?

- Our vision is sharpest during the day, thanks to millions of photoreceptor cells in the macula and fovea. In daylight, our color perception also works best. During the day, we can perceive the colors of objects vividly. It is only with night vision that our cones no longer work, and our sense of color deteriorates.

Night Vision—How Does It Work?

- When light fades, a different part of our visual system is used. When night falls or the lights are dimmed, night vision begins, and we perceive more shades of gray and less color. This happens because the fovea in the retina no longer provides high-resolution images to the brain. In the dark, the retina’s sensory cells are designed more for low-light conditions, and color cones play almost no role in this. Our eyes work with rods, and we see in low resolution and black-and-white. That’s why we can distinguish between colors much better during the day than at night. This also explains why we don’t see colors as well in the dark.

In darkness, our eyes dilate the pupils to let more light in and improve our vision. Our brain supports this adaptation: the human brain is capable of scanning our visual environment up to six times per second to help us see better in the dark. When we suddenly find ourselves in the dark, we are practically "blind" for the first few seconds. However, the pupils quickly adjust and expand to capture more light. This process takes about 30 minutes, and we are better able to perceive shadows and outlines. Although night vision varies from person to person, it is generally less accurate than daytime vision and does not provide as much detail.

Common Eye Problems and Diseases

Vision Disorders

- Vision disorders are common and vary from person to person. While some disorders may be temporary or treatable, others may be permanent and untreatable. However, many people use glasses or contact lenses to correct vision problems. The most common vision disorders are nearsightedness, farsightedness, astigmatism, and presbyopia (age-related farsightedness). These disorders usually develop gradually, but they are often treatable. Early diagnosis and treatment can help prevent further complications and improve vision.

Eye Infections

- Eye infections can cause various symptoms, such as redness, itching, swelling, and discharge. They can be caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi, or parasites. Common eye infections include conjunctivitis (pink eye), keratitis (corneal inflammation), uveitis (inflammation of the uvea), and blepharitis (inflammation of the eyelids). Eye infections can affect one or both eyes and can be mild or severe. Some infections may require medical treatment, while others may resolve on their own.

Cataracts

- Cataracts are a common age-related condition that affects the lens of the eye. They cause the lens to become cloudy, leading to blurred vision and difficulty seeing in low light. Cataracts usually develop slowly and can affect one or both eyes. In the early stages, cataracts may not cause any noticeable symptoms. However, as they progress, they can interfere with daily activities and reduce the quality of life. Cataract surgery is a common and effective treatment for this condition, where the cloudy lens is removed and replaced with an artificial lens.

Glaucoma

- Glaucoma is a group of eye diseases that damage the optic nerve, leading to vision loss and blindness if left untreated. It is often caused by increased pressure in the eye, known as intraocular pressure. Glaucoma can develop slowly over time (open-angle glaucoma) or suddenly (angle-closure glaucoma). Early detection and treatment are crucial to prevent permanent vision loss. Treatment options include medications, laser therapy, or surgery to lower the intraocular pressure and protect the optic nerve.

Macular Degeneration

- Macular degeneration is an age-related condition that affects the central part of the retina, known as the macula. It leads to the gradual loss of central vision, making it difficult to read, drive, and recognize faces. There are two types of macular degeneration: dry and wet. The dry form is more common and progresses slowly, while the wet form is less common but more severe and can cause rapid vision loss. Although there is no cure for macular degeneration, treatments are available to slow its progression and manage the symptoms.

Retinal Detachment

- Retinal detachment is a serious condition where the retina pulls away from its normal position at the back of the eye. This can cause sudden vision loss and requires immediate medical attention. Retinal detachment can be caused by injury, surgery, or underlying conditions such as diabetes or myopia (nearsightedness). Symptoms may include flashes of light, floaters, or a shadow over the visual field. Treatment options include laser surgery, cryotherapy, or a vitrectomy to reattach the retina and restore vision.

Conclusion

- The human eye is a remarkable organ that allows us to see and experience the world around us. Understanding its anatomy, structure, and function helps us appreciate its complexity and importance. However, the eyes are also vulnerable to various disorders and diseases that can affect our vision and quality of life. Regular eye exams and early detection are essential for maintaining healthy vision and preventing complications. By taking care of our eyes and seeking medical attention when needed, we can enjoy clear and vibrant vision for years to come.